I still remember the first time I tried to split a massive monolith into micro-frontends. It was late 2024. The promise was beautiful: independent deployments, faster builds, teams working in isolation without stepping on each other’s toes. I bought into the hype completely.

Then I actually tried to implement it with TypeScript and Webpack.

Three days later, I was staring at a CI pipeline that looked like a crime scene. Red crosses everywhere. The application ran fine locally (doesn’t it always?), but the moment it hit the staging environment, the host application panicked because it couldn’t find the type definitions for the remote modules. Or worse, the types were there, but they were stale, leading to runtime crashes because someone changed a prop name in the checkout micro-frontend without telling the shell application.

If you’re reading this, you’ve probably hit that same wall. You have a “Remote” app and a “Host” app. Webpack handles the JavaScript loading just fine via Module Federation. But TypeScript? TypeScript hates it. TypeScript wants to know everything at compile time, but Module Federation is inherently runtime-based. It’s a fundamental conflict.

The Async Trap (Or Why Your App Crashes on Startup)

Before we even talk about types, let’s talk about the most common mistake I see people make: synchronous imports. Webpack needs time to negotiate with the remote server to fetch the federated code. If you try to render your app immediately, it fails.

I wasted an entire afternoon debugging a blank white screen because I didn’t understand the “bootstrap” pattern. You can’t just have an index.ts that imports your app. You need an async boundary.

Here is the pattern that finally stabilized my entry point. It splits the initialization into a separate chunk, giving Webpack the breathing room it needs to load those remote entry files.

// index.ts

// This is your entry point. Note the dynamic import().

// This creates the necessary async boundary.

import('./bootstrap');

// bootstrap.tsx

import React from 'react';

import { createRoot } from 'react-dom/client';

import App from './App';

const container = document.getElementById('root');

if (!container) {

throw new Error('Failed to find the root element');

}

const root = createRoot(container);

// By the time this runs, Webpack has resolved the remote modules

root.render(

<React.StrictMode>

<App />

</React.StrictMode>

);It looks simple, right? But if you skip this and try to import App directly in index.ts, Webpack throws a “Shared module is not available for eager consumption” error that is incredibly vague.

The “Where Are My Types?” Problem

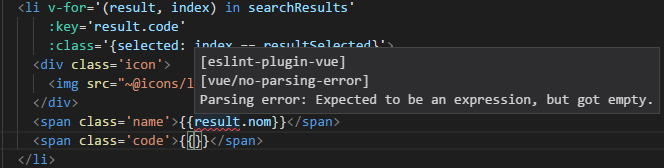

This is where things get messy. In a standard TypeScript project, you import a module, and VS Code immediately knows what that module exports. With Module Federation, you are importing something like checkout/PaymentForm. TypeScript looks at your node_modules, sees nothing, and screams.

For a long time, the “solution” was to manually write a declaration file (remotes.d.ts) that basically told TypeScript to shut up.

// remotes.d.ts

// The "I give up" approach

declare module 'checkout/PaymentForm' {

const PaymentForm: React.ComponentType<any>;

export default PaymentForm;

}I hate this. It defeats the entire purpose of using TypeScript. If I change a prop in the PaymentForm, the Host app has no idea. I shipped a bug to production last year exactly because of this—I renamed a prop, the build passed (because of the any type), and the checkout page broke for 10% of our users.

The better way—though it requires more setup—is to use the @module-federation/typescript plugin (or similar tools depending on your stack) to actually bundle the types.

But let’s say you are doing this manually to understand how it works. You need to configure Webpack to expose not just the JS, but also the structure. Here is a stripped-down version of a Webpack config that actually plays nice with dependencies:

// webpack.config.js

const ModuleFederationPlugin = require('webpack/lib/container/ModuleFederationPlugin');

const deps = require('./package.json').dependencies;

module.exports = {

// ... rest of config

plugins: [

new ModuleFederationPlugin({

name: 'host_app',

remotes: {

// The 'checkout' key here must match the import string in your app

checkout: 'checkout@http://localhost:3002/remoteEntry.js',

},

shared: {

...deps,

react: {

singleton: true,

requiredVersion: deps.react,

eager: true // Careful with this, but sometimes necessary for the host

},

'react-dom': {

singleton: true,

requiredVersion: deps['react-dom'],

},

},

}),

],

};Handling Runtime Failures Gracefully

Here is the reality check: Distributed systems fail. If your “Checkout” micro-frontend goes down, or the user is on a flaky connection and the script fails to load, your entire Host app shouldn’t crash.

You can’t rely on static imports. You need to wrap these remote components in boundaries. I wrote a wrapper function recently that handles the loading state and the error state. It saved my bacon during a partial outage last month.

// RemoteWrapper.tsx

import React, { Suspense } from 'react';

// A simple error boundary class component

class ErrorBoundary extends React.Component<{children: React.ReactNode}, {hasError: boolean}> {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { hasError: false };

}

static getDerivedStateFromError() {

return { hasError: true };

}

render() {

if (this.state.hasError) {

return <div className="p-4 bg-red-100 text-red-800">Module failed to load.</div>;

}

return this.props.children;

}

}

// Practical usage of lazy loading a federated module

// We cast it to a generic type because TS still struggles to infer remote types automatically

const RemoteButton = React.lazy(() => import('checkout/Button') as Promise<{ default: React.ComponentType<any> }>);

export const SafeRemoteButton = () => (

<ErrorBoundary>

<Suspense fallback={<div>Loading remote component...</div>}>

<RemoteButton onClick={() => console.log('Remote code executed!')} />

</Suspense>

</ErrorBoundary>

);Notice the as Promise<...> cast? That’s the dirty little secret. Unless you have a sophisticated type-syncing pipeline running in your CI, you often have to cast the import to satisfy the compiler locally. It’s not perfect, but it lets you keep moving.

The CI/CD Nightmare

The hardest lesson I learned wasn’t about code; it was about deployment order. If you deploy the Host app before the Remote app, and the Host expects a new version of a federated module that doesn’t exist yet, you break production.

We eventually moved to a “Blue/Green” deployment strategy for our micro-frontends. We deploy the remotes first, verify they are live, and only then do we trigger the build for the host application. It sounds obvious in hindsight, but when you’re trying to set up GitHub Actions for 15 different repos, it’s easy to miss.

Also, version locking. In the Webpack config above, I used requiredVersion: deps.react. Do not ignore this. If your Host uses React 19 and your Remote uses React 18, and you try to share the singleton, weird things happen. Event listeners detach. Hooks stop working. I spent three days debugging a useEffect that wouldn’t fire, only to realize the Remote was pulling in its own copy of React because the versions didn’t satisfy the semver requirement.

Is It Worth It?

Honestly? Sometimes I miss the monolith. It was simple. You compiled it, and if it compiled, it worked.

But then I look at our build times. Our main dashboard used to take 15 minutes to build. Now, the shell app builds in 40 seconds. We can deploy a fix to the reporting module without redeploying the entire authentication stack. That flexibility is powerful, but you pay for it with complexity. You pay for it with configuration hell and TypeScript gymnastics.

If you’re going down this road, don’t just copy-paste the Webpack config and hope for the best. Understand the network requests. Understand how the remoteEntry.js file works. And for the love of code, set up proper error boundaries, because that remote file will fail to load eventually.