I have a confession to make. I still see developers—smart, experienced developers—typing their function arguments as any just to silence the compiler. It’s late 2025, and frankly, we should be past this. If you are going to use TypeScript, you might as well use it to actually protect your code, not just as a linter that you fight against.

The beauty of TypeScript Functions isn’t just about catching bugs; it’s about the mental model. I realized recently that whether I’m writing a quick event handler for a button in the DOM or a complex serverless handler for a backend API, the approach is identical. It’s strictly about defining the contract: what comes in and what goes out. Once you lock that down, the implementation details inside the function become much less stressful to manage.

I want to walk through how I handle functions in my daily work. I’m skipping the “Hello World” stuff you can find in any TypeScript Tutorial. Instead, I’m focusing on the patterns that actually clean up your codebase and make your life easier when you’re staring at a screen at 2 AM trying to figure out why your payload is undefined.

The Basics: Explicit vs. Implicit

TypeScript Type Inference is magical, but I don’t trust it blindly, especially with function returns. While TypeScript is great at guessing what a function returns based on the code inside, I prefer to be explicit. Why? Because it prevents accidental API changes.

If I change the internal logic of a function and accidentally return a string instead of a number, I want the error to be inside the function, not where the function is called. Explicit return types act as a guardrail for my future self.

Here is a standard setup I use for TypeScript Arrow Functions. Note the explicit return type:

interface UserMetrics {

id: number;

score: number;

isActive: boolean;

}

// I always define the return type explicitly (: number)

const calculateScore = (metrics: UserMetrics, bonus: number = 0): number => {

if (!metrics.isActive) {

return 0;

}

return metrics.score + bonus;

};

// If I accidentally try to return a string here, TS yells at me immediately.

// const badFunction = (): number => "string"; // ErrorThis falls under TypeScript Best Practices 101 for me. It also helps with TypeScript Documentation generation if you use tools that parse your code.

Async Functions and APIs

Handling asynchronous operations is where I see the most mess. People often forget that an async function always returns a Promise. When dealing with TypeScript Async patterns, you need to wrap your return type in Promise<T>.

I do a lot of work with TypeScript Node.js integration, and fetching data from an external API is a daily task. I use a generic wrapper pattern to keep my API calls clean. This leverages TypeScript Generics to ensure that my fetch function knows exactly what data shape to expect back.

interface ApiResponse<T> {

data: T;

status: number;

message?: string;

}

interface UserProfile {

username: string;

email: string;

role: 'admin' | 'user' | 'guest'; // TypeScript Union Types

}

// A generic fetcher function

async function fetchData<T>(url: string): Promise<ApiResponse<T>> {

const response = await fetch(url);

// In a real app, I'd add better error handling here

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(Failed to fetch: ${response.statusText});

}

const json = await response.json();

return json as ApiResponse<T>; // TypeScript Type Assertions

}

// Usage

const getUser = async (userId: string): Promise<void> => {

try {

const result = await fetchData<UserProfile>(/api/users/${userId});

// TypeScript knows 'result.data' is UserProfile

console.log(result.data.username.toUpperCase());

} catch (error) {

// Handling TypeScript Errors in catch blocks

if (error instanceof Error) {

console.error(error.message);

}

}

};Notice the use of TypeScript Union Types for the role. This is infinitely better than using a string. If I check if (user.role === 'superadmin'), TypeScript will immediately flag it as an error because ‘superadmin’ isn’t in the union. This level of safety is why I stick with TypeScript Strict Mode in my tsconfig.json.

DOM Manipulation and Event Handlers

When working on the frontend, perhaps migrating TypeScript JavaScript to TypeScript, DOM events are a pain point. The default Event type is too generic. You usually need to know that the target is an HTMLInputElement to access .value.

I avoid using as assertions inside the handler if I can help it. Instead, I try to type the event correctly from the start. However, sometimes TypeScript Type Assertions are unavoidable when dealing with the DOM because the compiler can’t see your HTML structure.

// Handling a form submission

const handleLogin = (event: SubmitEvent): void => {

event.preventDefault();

// We need to tell TS what the target actually is

const form = event.target as HTMLFormElement;

const emailInput = form.elements.namedItem('email') as HTMLInputElement;

if (emailInput) {

console.log(Logging in with ${emailInput.value});

}

};

// Attaching to a button click

const setupButton = (): void => {

const btn = document.querySelector('#submit-btn');

// Type Guard check

if (btn instanceof HTMLButtonElement) {

btn.addEventListener('click', (e: MouseEvent) => {

console.log('Button clicked at coordinates:', e.clientX, e.clientY);

});

}

};This pattern ensures strict type safety. If I tried to access e.value on that MouseEvent, TypeScript VS Code integration would underline it in red instantly. This saves me from refreshing the browser just to see “undefined” in the console.

Advanced Patterns: Overloads and Guards

Sometimes a function needs to behave differently based on the input. In JavaScript, you just check arguments dynamically. In TypeScript, we use function overloads. I don’t use these often, but when I do, they clean up the API surface significantly.

Let’s say I have a utility that formats dates. It might take a timestamp (number) or a date string. I want to define specific return types based on input.

// Overload signatures

function formatData(input: number): string;

function formatData(input: string): string[];

function formatData(input: number | string): string | string[] {

if (typeof input === 'number') {

return new Date(input).toISOString();

} else {

return input.split('-');

}

}

const dateStr = formatData(1735200000000); // Returns string

const dateParts = formatData("2025-12-26"); // Returns string[]This utilizes TypeScript Union Types in the implementation but gives the caller a very specific type. It’s a powerful way to make your TypeScript Libraries or internal utilities easier to consume.

Another critical concept is TypeScript Type Guards. I use these constantly to narrow down types at runtime. It’s the bridge between the static compile-time world and the dynamic runtime world.

interface Admin {

role: 'admin';

permissions: string[];

}

interface User {

role: 'user';

email: string;

}

type Person = Admin | User;

// Custom Type Guard

function isAdmin(person: Person): person is Admin {

return person.role === 'admin';

}

const performAction = (person: Person) => {

if (isAdmin(person)) {

// TypeScript knows 'person' is Admin here

console.log(person.permissions.join(', '));

} else {

// TypeScript knows 'person' is User here

console.log(person.email);

}

};Configuration and Tooling

None of this matters if your TypeScript Configuration is loose. I always set "strict": true in my tsconfig.json. It forces you to handle null and undefined, which are the source of 90% of runtime errors I encounter.

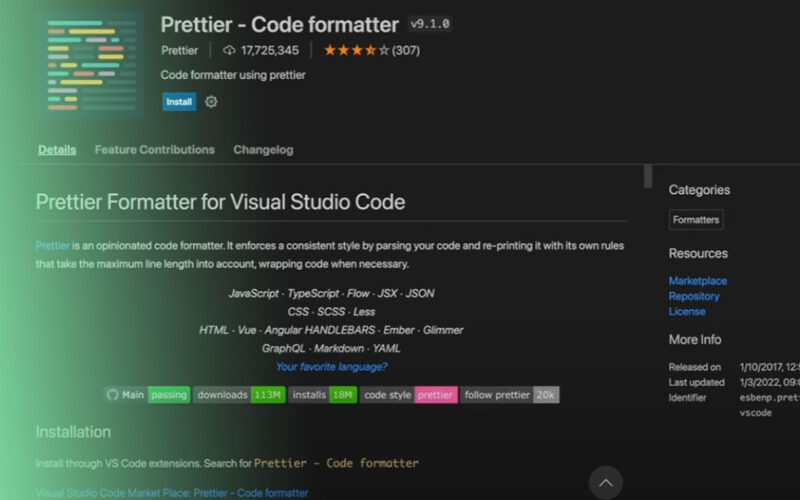

I also rely heavily on TypeScript ESLint and TypeScript Prettier. I configure ESLint to ban the any type explicitly. It sounds harsh, but it forces the team to think about data structures. If you truly don’t know the type, unknown is a safer alternative because it forces you to check the type before using it.

For building, whether I’m using TypeScript Webpack or newer tools like TypeScript Vite, the process is seamless now. The compilation speed in 2025 is incredible compared to where we were a few years ago.

The Mental Model Shift

When I moved from writing pure JavaScript to TypeScript, the hardest part wasn’t the syntax—it was the discipline. In TypeScript React projects, for example, defining Props interfaces feels tedious at first. But then you come back to the component six months later, and you know exactly what it needs.

This applies to backend work too. If I’m building a serverless function, I treat the event object just like function arguments. I define an interface for the incoming JSON body. I define an interface for the response. It turns the “wild west” of HTTP requests into a predictable function call.

I’ve found that TypeScript Utility Types like Partial<T>, Pick<T>, and Omit<T> are essential here. They allow you to reuse your base interfaces without rewriting them for every slight variation (like a patch request vs. a post request).

interface Product {

id: string;

name: string;

price: number;

description: string;

}

// For creating a product, we don't need ID (generated by DB)

type CreateProductDTO = Omit<Product, 'id'>;

// For updating, everything is optional

type UpdateProductDTO = Partial<CreateProductDTO>;

function updateProduct(id: string, changes: UpdateProductDTO) {

// Logic to update product

console.log(Updating ${id}, changes);

}Final Thoughts

Writing robust TypeScript Functions is about more than just syntax; it’s about communicating intent. When I read your code, the function signature should tell me a story. It should tell me what dependencies it needs and exactly what it produces.

If you are still struggling with TypeScript Debugging or fighting the compiler, take a step back. Are you trying to force dynamic JavaScript patterns into a static system? Simplify your data flow. Define your types first, then write the function. It might feel slower initially, but I promise you, the time you save on maintenance is worth every second.