Introduction

The landscape of server-side JavaScript has undergone a massive transformation over the last decade. While JavaScript remains the engine of the web, TypeScript has become the steering wheel, providing the safety, structure, and scalability required for modern enterprise applications. For developers building with TypeScript Node.js, the ecosystem is currently experiencing a paradigm shift. Historically, running TypeScript required a build step using the TypeScript Compiler (tsc) or loaders like ts-node. However, recent advancements in the Node.js runtime are paving the way for native TypeScript execution, fundamentally changing how we approach TypeScript Development.

This evolution brings TypeScript Best Practices into sharp focus. It is no longer just about writing code that compiles; it is about writing code that is “erasable”—types that can be stripped away efficiently by the runtime without affecting the underlying JavaScript logic. This article serves as a comprehensive TypeScript Tutorial, guiding you through the essentials of setting up a robust environment, migrating from JavaScript to TypeScript, and leveraging advanced features like TypeScript Generics and TypeScript Utility Types. Whether you are using TypeScript Express, TypeScript NestJS, or building standalone microservices, understanding the nuances of TypeScript vs JavaScript in a Node environment is critical for performance and maintainability.

Section 1: Core Concepts and Modern Configuration

Setting Up the Environment

Before diving into complex logic, a proper foundation is essential. A TypeScript Project relies heavily on the tsconfig.json file. This configuration dictates how the TypeScript Compiler interprets your code. In modern Node.js development, particularly with the push toward native execution, strictness is key. Enabling TypeScript Strict Mode ensures that null and undefined are handled explicitly, reducing runtime errors significantly.

When configuring your project, you must decide between CommonJS and ES Modules (ESM). Modern Node.js development strongly favors ESM. This affects how you handle TypeScript Modules and imports. Below is a practical example of a modern configuration that aligns with current standards, preparing your codebase for tools like TypeScript Vite or native Node execution.

Here is a robust setup for a TypeScript Node.js application:

// tsconfig.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"target": "ES2022",

"module": "NodeNext",

"moduleResolution": "NodeNext",

"strict": true,

"esModuleInterop": true,

"skipLibCheck": true,

"forceConsistentCasingInFileNames": true,

"outDir": "./dist",

"rootDir": "./src",

"verbatimModuleSyntax": true

},

"include": ["src/**/*"],

"exclude": ["node_modules", "**/*.spec.ts"]

}Type Definitions and Explicit Imports

One of the most critical habits to form—especially for compatibility with modern runtimes—is the use of explicit type imports. When you import TypeScript Interfaces or TypeScript Types, using the type keyword explicitly tells the compiler (and the runtime stripper) that these lines can be safely removed during the build process. This separates your runtime code from your design-time code.

Furthermore, developers often debate TypeScript Enums versus object literals. While Enums are a staple in languages like C# or Java, in the JavaScript world, they generate extra code that can complicate native execution. A modern best practice is to avoid Enums in favor of TypeScript Union Types derived from immutable objects (using as const). This approach leverages TypeScript Type Inference to create safer, cleaner code.

TypeScript and Webpack logos – TypeScript Webpack | How to Create TypeScript Webpack with Project?

Let’s look at a practical example of creating a typed API response handler using Arrow Functions TypeScript and explicit type imports:

// src/types/api.ts

export interface ApiResponse<T> {

success: boolean;

data: T;

timestamp: number;

}

export type UserRole = 'ADMIN' | 'EDITOR' | 'VIEWER';

// src/utils/responseHandler.ts

import type { ApiResponse, UserRole } from '../types/api.js';

import { IncomingMessage, ServerResponse } from 'node:http';

// Practical example of avoiding Enums using 'as const'

export const HTTP_STATUS = {

OK: 200,

BAD_REQUEST: 400,

UNAUTHORIZED: 401,

SERVER_ERROR: 500

} as const;

export type HttpStatus = typeof HTTP_STATUS[keyof typeof HTTP_STATUS];

export const sendJson = <T>(

res: ServerResponse,

data: T,

statusCode: HttpStatus = HTTP_STATUS.OK

): void => {

const response: ApiResponse<T> = {

success: statusCode >= 200 && statusCode < 300,

data,

timestamp: Date.now()

};

res.writeHead(statusCode, { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' });

res.end(JSON.stringify(response));

};Section 2: Implementation and Async Patterns

Async TypeScript and Promises

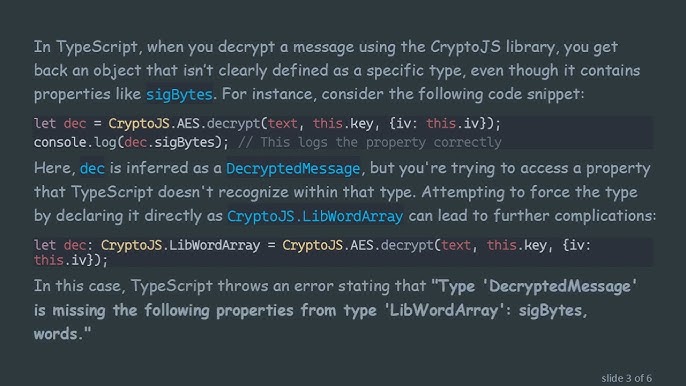

Node.js is asynchronous by nature. Mastering Async TypeScript and Promises TypeScript is non-negotiable. When fetching data from a database or an external API, you need to ensure the data flowing into your application matches your expectations. This is where TypeScript Type Assertions and generic return types come into play. However, blindly asserting types can be dangerous. It is often better to use TypeScript Type Guards or validation libraries like Zod to ensure runtime safety.

In the context of TypeScript Webpack builds or native execution, handling errors in async functions requires careful typing. The unknown type is safer than any for error catching blocks, forcing you to perform checks before accessing error properties. This aligns with TypeScript Strict Mode principles.

Real-world Example: Fetching and Parsing Data

The following example demonstrates a service that fetches user data. It utilizes TypeScript Classes (though functional approaches are also popular) and demonstrates how to handle external API data safely. We will simulate a scenario where we might need to process data for a frontend, touching upon the concept of preparing data for the DOM (Document Object Model) consumption, even though we are on the server.

// src/services/UserService.ts

import type { IncomingMessage } from 'node:http';

// Define the shape of the external data

interface ExternalUser {

id: number;

name: string;

email: string;

company: {

name: string;

catchPhrase: string;

};

}

// Define our internal application model

interface UserProfile {

userId: string;

displayName: string;

organization: string;

}

export class UserService {

private readonly baseUrl: string;

constructor(baseUrl: string) {

this.baseUrl = baseUrl;

}

// Async function with Generic Return Type

public async getUserById(id: number): Promise<UserProfile | null> {

try {

// Native fetch is available in Node.js 18+

const response = await fetch(`${this.baseUrl}/users/${id}`);

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(`Failed to fetch user: ${response.statusText}`);

}

// We cast to unknown first, then validate (simplified here for brevity)

const rawData = await response.json() as unknown;

if (this.isExternalUser(rawData)) {

return this.transformUser(rawData);

}

return null;

} catch (error: unknown) {

// Type Guard for Error objects

if (error instanceof Error) {

console.error(`Error in UserService: ${error.message}`);

}

throw error;

}

}

// Custom Type Guard

private isExternalUser(data: any): data is ExternalUser {

return data && typeof data.id === 'number' && typeof data.email === 'string';

}

// Data transformation

private transformUser(user: ExternalUser): UserProfile {

return {

userId: user.id.toString(),

displayName: user.name,

organization: user.company.name

};

}

}Section 3: Advanced Techniques and Native Execution

The Shift to Native TypeScript

The most exciting development in the ecosystem is the move toward running TypeScript natively in Node.js. This involves features like “type stripping,” where the runtime simply erases type annotations and executes the remaining JavaScript. To leverage this, developers must adhere to specific TypeScript Tips. Specifically, you should avoid language features that require transpilation into runtime code that doesn’t exist in standard JavaScript.

TypeScript Enums, TypeScript Namespaces, and parameter properties in constructors are features that generate runtime artifacts. To write “future-proof” TypeScript for Node.js, you should prefer standard JavaScript patterns with type annotations over TypeScript-specific runtime features. This makes your code more portable and easier to debug.

Advanced Types: Intersection and Utility Types

TypeScript and Webpack logos – How to Setup a React App with TypeScript + Webpack from Scratch …

To build scalable applications, you must master TypeScript Intersection Types and TypeScript Utility Types (like Partial, Omit, and Pick). These allow you to compose complex types from simple ones, adhering to the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle.

Below is an example of a generic repository pattern. This is common in TypeScript NestJS or large TypeScript Express applications. It demonstrates TypeScript Generics to create a reusable database abstraction.

// src/database/Repository.ts

// A generic interface for any entity stored in DB

interface BaseEntity {

id: string;

createdAt: Date;

updatedAt: Date;

}

// Utility type to remove system fields for creation DTOs

type CreateDto<T> = Omit<T, keyof BaseEntity>;

// Utility type for updates (everything optional except ID)

type UpdateDto<T> = Partial<Omit<T, 'id'>> & { id: string };

export class InMemoryRepository<T extends BaseEntity> {

private storage: Map<string, T> = new Map();

async create(data: CreateDto<T>): Promise<T> {

const id = crypto.randomUUID();

const now = new Date();

// We have to cast here because T includes BaseEntity fields

// In a real app, an ORM handles this mapping

const entity = {

...data,

id,

createdAt: now,

updatedAt: now,

} as T;

this.storage.set(id, entity);

return entity;

}

async findById(id: string): Promise<T | undefined> {

return this.storage.get(id);

}

async update(data: UpdateDto<T>): Promise<T> {

const existing = await this.findById(data.id);

if (!existing) {

throw new Error(`Entity with ID ${data.id} not found`);

}

const updated = {

...existing,

...data,

updatedAt: new Date()

};

this.storage.set(data.id, updated);

return updated;

}

}Section 4: Best Practices and Optimization

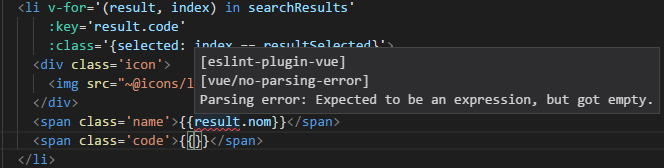

Linting and Formatting

Maintaining code quality in a TypeScript Project requires automated tools. TypeScript ESLint and TypeScript Prettier are the industry standards. They enforce consistency and catch errors that the compiler might miss. For example, ESLint can be configured to forbid the use of any, enforcing TypeScript Best Practices. It can also enforce the use of import type, which, as discussed, is crucial for modern Node.js environments.

Testing with TypeScript

Testing is vital. Jest TypeScript (via ts-jest) is a popular combination. However, newer test runners in Node.js are starting to support TypeScript natively. When writing TypeScript Unit Tests, you often need to mock dependencies. The typing system helps ensure your mocks align with the actual implementations.

TypeScript and Webpack logos – How to use p5.js with TypeScript and webpack – DEV Community

Performance and Build Tools

While tsc is the default compiler, tools like TypeScript Vite, esbuild, or SWC offer significantly faster compilation speeds for development. However, for production builds, checking types via tsc --noEmit is still recommended to catch type errors before deployment. When optimizing TypeScript Performance, consider the cost of complex types. deeply nested recursive types can slow down the editor and the build process. Keep your types flat and simple where possible.

Finally, avoid “pollution” in your global scope. Use TypeScript Modules effectively. If you are migrating from JavaScript to TypeScript, do it incrementally. Enable allowJs in your configuration and migrate file by file, increasing strictness as you go.

Conclusion

TypeScript Node.js development has reached a maturity level that makes it the default choice for serious backend development. We are moving away from complex build chains toward a future where Node.js understands TypeScript syntax natively. By adhering to the principles outlined in this article—avoiding Enums, using explicit type imports, leveraging TypeScript Generics, and maintaining strict configuration—you ensure your applications are robust, scalable, and ready for the next generation of JavaScript runtimes.

Whether you are building a simple API with TypeScript Express or a complex microservice architecture with TypeScript NestJS, the key is to embrace the type system not just as a linter, but as a design tool. As you continue your journey, keep exploring TypeScript Tools and stay updated with the Node.js release cycle, as the gap between writing TypeScript and running it is closing faster than ever.