I’m tired of hearing developers complain that TypeScript makes their application slow. It doesn’t. TypeScript disappears the moment you build your project. If your app feels sluggish in the browser or your Node.js server is choking on requests, that’s not because of types; it’s because of the JavaScript code you wrote, or perhaps how you configured the compiler to emit that code.

I recently audited a legacy codebase where the team was convinced they needed to rewrite everything in Rust because “TypeScript is too heavy.” After spending two days refactoring their generic implementations and fixing their build pipeline, we cut their runtime overhead by 40%. The problem wasn’t the language; it was the implementation.

Performance in TypeScript is a two-fold conversation. First, there’s the development performance (how fast your IDE runs and how quickly tsc checks your code). Second, and more importantly, there’s the runtime performance of the emitted JavaScript. I want to focus on the latter today, with a bit of advice on the former, because shipping slow code is a much bigger sin than waiting an extra two seconds for a build.

The Runtime Reality: It’s Just JavaScript

When I teach TypeScript Basics to juniors, the first thing I hammer home is that the browser has no idea what an interface is. V8 (the engine in Chrome and Node) only sees JavaScript. This means your TypeScript Performance strategy is actually just a JavaScript performance strategy, enforced by a type system.

However, TypeScript offers features that can accidentally hurt you if you aren’t careful. A classic example involves TypeScript Enums. I generally avoid standard enums because they generate a lot of IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression) boilerplate in the output. Instead, I use const enum or union types, which vanish completely during compilation.

Here is how I structure high-performance constants to ensure zero runtime overhead:

// ❌ AVOID: Standard Enums often generate extra code

// enum Status {

// Active,

// Inactive

// }

// ✅ BETTER: Union Types with string literals

// Zero runtime overhead, just string comparisons

type Status = 'active' | 'inactive';

// ✅ BEST (for numbers): Const Enums

// These are inlined at compile time

const enum StatusCode {

Success = 200,

BadRequest = 400,

ServerError = 500

}

function handleResponse(code: StatusCode): void {

if (code === StatusCode.Success) {

console.log("All good");

}

}

// The compiled JS just sees: if (code === 200)Optimizing Async Operations and API Calls

In TypeScript Node.js environments, I often see performance bottlenecks in how asynchronous code is handled. The type system gives us a false sense of security. Just because the return type is correct doesn’t mean the execution flow is efficient.

A pattern I see constantly is the “waterfall” effect, where developers await promises sequentially inside a loop. This kills performance. I use TypeScript Generics to create reusable, concurrent handlers for my API calls.

Here is a utility I use to handle batch processing. It leverages TypeScript Promises to run operations in parallel while maintaining strict type safety on the return values.

interface UserData {

id: number;

username: string;

role: 'admin' | 'user';

}

// A simulated API call with a generic return type

const fetchUser = async (id: number): Promise<UserData> => {

// Simulating network delay

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 50));

return { id, username: user_${id}, role: 'user' };

};

// ❌ SLOW: Sequential processing

async function processSequentially(ids: number[]) {

const results: UserData[] = [];

for (const id of ids) {

// This waits for each request to finish before starting the next

const user = await fetchUser(id);

results.push(user);

}

return results;

}

// ✅ FAST: Parallel processing with Promise.all

async function processInParallel(ids: number[]): Promise<UserData[]> {

// We map the IDs to an array of Promises immediately

const promises = ids.map(id => fetchUser(id));

// TypeScript correctly infers the return type as UserData[]

return Promise.all(promises);

}

// Usage

const userIds = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

processInParallel(userIds).then(users => {

console.log(Fetched ${users.length} users efficiently.);

});By defining the UserData interface, I ensure that my consumption of the data is safe. TypeScript Type Inference handles the rest. If I tried to access user.email in the resulting array, TypeScript Strict Mode would yell at me immediately, saving me runtime debugging hours.

DOM Manipulation and Event Listeners

When working with TypeScript React or vanilla DOM manipulation, performance usually drops due to excessive re-renders or heavy event listeners. One specific area where TypeScript helps me optimize is strictly typing event handlers to ensure I’m not accessing properties that trigger reflows unnecessarily.

I frequently use TypeScript Type Guards to ensure the elements I’m interacting with are exactly what I expect them to be. This prevents runtime errors, but it also allows the JavaScript engine to optimize the code path because the shape of the object is predictable.

Here is a practical example of a debounced search input. I see people import heavy libraries like Lodash for this, but writing a typed utility is lighter and faster.

// A generic debounce function type

type AnyFunction = (...args: any[]) => void;

function debounce<T extends AnyFunction>(func: T, wait: number): (...args: Parameters<T>) => void {

let timeout: ReturnType<typeof setTimeout> | null = null;

return (...args: Parameters<T>) => {

if (timeout) clearTimeout(timeout);

timeout = setTimeout(() => {

func(...args);

}, wait);

};

}

// Typed DOM interaction

const searchInput = document.getElementById('search-box') as HTMLInputElement;

if (searchInput) {

const handleInput = (event: Event) => {

const target = event.target as HTMLInputElement;

console.log(Searching for: ${target.value});

// Expensive DOM update or API call here

};

// Applying the debounce

const optimizedHandler = debounce(handleInput, 300);

searchInput.addEventListener('input', optimizedHandler);

}This snippet demonstrates TypeScript Utility Types like Parameters and ReturnType. Instead of using any, which defeats the purpose of TypeScript, I preserve the argument types of the function being debounced. This is crucial for TypeScript Development at scale; you want your utilities to be as type-safe as your business logic.

The Build Chain: Vite vs. TSC

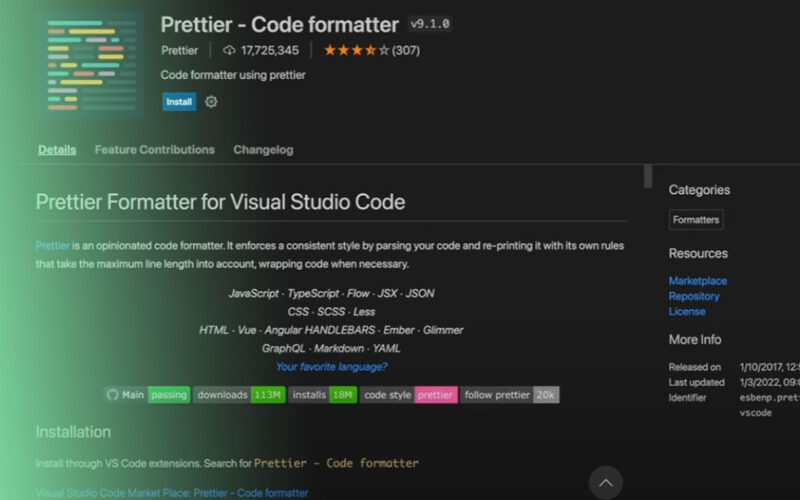

In 2025, if you are still using tsc (the TypeScript Compiler) to transpile your code for development, you are wasting time. TypeScript Tools have evolved. I use TypeScript Vite for almost all my web projects now. Vite uses esbuild, which is written in Go, to transpile TypeScript to JavaScript instantly.

However, esbuild strips types; it doesn’t check them. This is a trade-off I happily make. I run tsc --noEmit in a separate terminal window or as a pre-commit hook to catch TypeScript Errors. This separation of concerns—transpilation for speed, compilation for type checking—is the modern standard.

When configuring your TypeScript TSConfig, enabling the "skipLibCheck": true option is a must. It stops the compiler from checking all the declaration files in your node_modules folder, which significantly speeds up the build time. Unless you are maintaining a library, you usually don’t care if a dependency has a type error deep in its definitions.

Advanced Types: The Double-Edged Sword

I love TypeScript Advanced features. TypeScript Conditional Types and Mapped Types allow for incredible flexibility. But I have crashed my VS Code server more times than I can count by writing recursive types that are too complex.

Complex types don’t affect runtime performance (again, they are erased), but they destroy TypeScript Debugging and development velocity. If your IntelliSense takes 5 seconds to pop up, you are losing flow.

Here is an example of a useful, but computationally light, advanced type helper I use for TypeScript API responses. It helps me visualize data structures without killing the compiler.

// A utility to make specific properties optional

// Great for PATCH requests where you don't need the full object

type PartialBy<T, K extends keyof T> = Omit<T, K> & Partial<Pick<T, K>>;

interface Article {

id: number;

title: string;

content: string;

author: string;

publishedDate: Date;

}

// For updating, we might require ID but everything else is optional

type UpdateArticleDto = PartialBy<Article, 'title' | 'content' | 'author' | 'publishedDate'>;

function updateArticle(payload: UpdateArticleDto) {

// Payload.id is required

// Payload.title is optional

console.log(Updating article ${payload.id});

}Using TypeScript Union Types and TypeScript Intersection Types effectively reduces the amount of defensive programming you have to write. If the types guarantee a certain shape, you don’t need runtime checks for every single property, which slims down your final bundle.

Migration and Hygiene

For teams moving from TypeScript JavaScript to TypeScript, the temptation to use any is strong. Don’t do it. Using any de-optimizes V8 because the engine can’t predict the object shape. If you must be flexible, use unknown and enforce TypeScript Type Assertions or guards before using the data.

I also rely heavily on TypeScript ESLint and TypeScript Prettier. While they are linting tools, they catch patterns that lead to performance leaks, such as unused variables or incorrect dependency arrays in React hooks. I configure my rules to be strict. TypeScript Best Practices aren’t just suggestions; they are the guardrails that keep your app fast.

Final Thoughts on Optimization

If you are building TypeScript Projects in late 2025, you have access to an incredible ecosystem. TypeScript Frameworks like TypeScript NestJS or Next.js have baked-in optimizations that leverage the type system for better builds.

My advice? Stop worrying about the compiler overhead and start worrying about your data structures and algorithmic complexity. TypeScript is a tool for correctness, and correctness often leads to performance because you aren’t writing code to handle impossible states. Use TypeScript Unit Tests with TypeScript Jest to verify your logic, use TypeScript Strict Mode to force discipline, and trust the process.

The next time your app feels slow, check your loops, check your renders, and check your network calls. The .ts file extension isn’t the villain; it’s usually the hero trying to save you from yourself.