Introduction

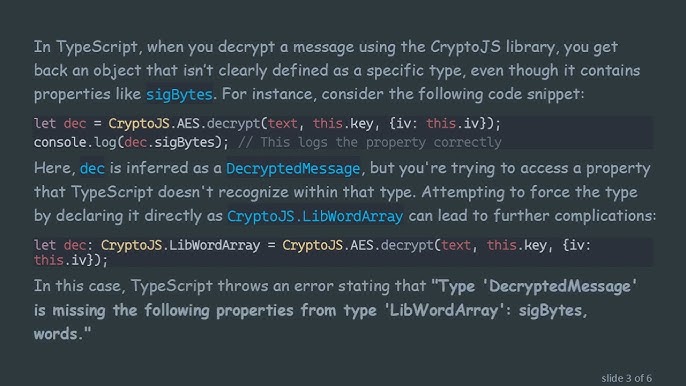

The landscape of modern web development has shifted dramatically over the last decade. While JavaScript remains the undisputed language of the web, the complexity of modern applications—ranging from compact data processing libraries to massive enterprise platforms—has exposed the limitations of dynamic typing. This is where TypeScript enters the conversation. As projects scale, the lack of type safety in JavaScript often leads to runtime errors that are difficult to trace, especially when dealing with complex data structures like LLM outputs or intricate API responses.

Migrating from JavaScript to TypeScript is no longer just a trend; it is a standard industry practice for ensuring code stability and maintainability. TypeScript, a superset of JavaScript, adds static definitions that allow developers to catch errors during development rather than in production. Whether you are working on TypeScript React applications, TypeScript Node.js backends, or developing high-performance utility libraries, the transition offers immediate benefits in developer experience through better tooling and IntelliSense.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the journey of adopting TypeScript. We will cover TypeScript Basics, move through TypeScript Advanced concepts, and look at practical implementations involving APIs and the DOM. By the end, you will understand why frameworks like TypeScript NestJS, TypeScript Angular, and TypeScript Vue have made strict typing a default, and how you can leverage these benefits in your own projects.

Section 1: Core Concepts and The Type System

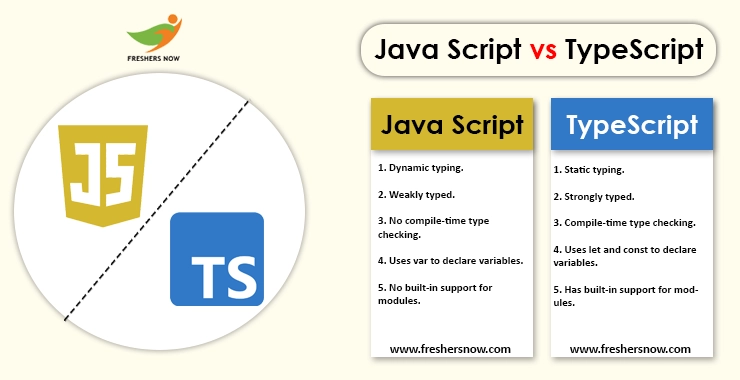

The fundamental difference between JavaScript and TypeScript lies in how they handle data types. JavaScript utilizes dynamic typing, meaning variables can change types at runtime without warning. TypeScript introduces a structural type system that enforces constraints at compile time. This is particularly crucial when building libraries that handle data serialization or compact formats, where a single type mismatch can corrupt an entire dataset.

Understanding Basic Types and Interfaces

At the heart of TypeScript Migration is the concept of defining the shape of your data. In JavaScript, you might pass an object to a function and hope it has the correct properties. In TypeScript, you define TypeScript Interfaces or Types to guarantee it.

Let’s look at a practical scenario: a function that processes user data. In standard JavaScript, this function is prone to silent failures if a property is missing.

// JavaScript Version (prone to errors)

function calculateUserMetrics(user) {

// If user.stats is undefined, this throws an error at runtime

return user.stats.visits * user.stats.conversionRate;

}

// We might accidentally pass:

calculateUserMetrics({ name: "John", stats: "N/A" }); // NaN or CrashNow, let’s refactor this using TypeScript Interfaces and TypeScript Types. We will enforce the structure of the user object, ensuring that `stats` always exists and contains numbers.

// TypeScript Version

interface UserStats {

visits: number;

conversionRate: number;

}

interface User {

id: string;

username: string;

stats: UserStats;

isActive?: boolean; // Optional property

}

const calculateUserMetrics = (user: User): number => {

return user.stats.visits * user.stats.conversionRate;

};

// Usage

const validUser: User = {

id: "u_123",

username: "dev_guru",

stats: {

visits: 100,

conversionRate: 0.05

}

};

console.log(calculateUserMetrics(validUser)); // Output: 5

// The TypeScript Compiler will flag this as an error immediately:

// calculateUserMetrics({ username: "bad_input" }); // Error: Property 'stats' is missingType Inference and Functions

One of the best features for beginners is TypeScript Type Inference. You don’t always need to explicitly annotate every variable. If you initialize a variable as a string, TypeScript knows it is a string. However, for TypeScript Functions, explicit return types are a TypeScript Best Practice. It ensures the function returns exactly what you expect, preventing accidental return of `undefined`.

Section 2: Implementation Details – Async Data and APIs

TypeScript and Webpack logos – TypeScript Webpack | How to Create TypeScript Webpack with Project?

Modern web development relies heavily on asynchronous operations. When fetching data from an API—perhaps processing output from an LLM or a compact binary format—knowing the shape of the response is critical. In JavaScript, developers often guess the structure of the JSON response. In TypeScript, we use TypeScript Generics to create flexible, type-safe fetch wrappers.

Handling Async/Await with Generics

Async TypeScript works identically to JavaScript at runtime, but with added compile-time safety. By using Promises TypeScript features, we can define exactly what a Promise resolves to. This is incredibly useful when working with TypeScript Node.js or frontend frameworks like TypeScript React.

Below is a robust example of a generic API handler. This pattern allows you to reuse the fetch logic for different data types (e.g., User, Product, or Configuration) while maintaining strict type safety.

// Define the shape of a generic API response

interface ApiResponse<T> {

data: T;

status: number;

message: string;

}

interface Product {

id: number;

name: string;

price: number;

tags: string[];

}

// A generic fetch wrapper

async function fetchData<T>(url: string): Promise<ApiResponse<T>> {

try {

const response = await fetch(url);

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(`HTTP error! status: ${response.status}`);

}

// In a real app, you might use a library like Zod here for runtime validation

const json = await response.json();

return {

data: json as T, // Type Assertion

status: response.status,

message: "Success"

};

} catch (error) {

// Handling TypeScript Errors properly

const errorMessage = error instanceof Error ? error.message : "Unknown error";

throw new Error(`Fetch failed: ${errorMessage}`);

}

}

// Usage Example

async function loadProduct() {

try {

// We pass <Product> to the generic, so TypeScript knows 'result.data' is a Product

const result = await fetchData<Product>('https://api.example.com/products/1');

// IntelliSense works here! It knows 'price' exists and is a number.

console.log(`Product Price: $${result.data.price.toFixed(2)}`);

} catch (e) {

console.error(e);

}

}In this example, the use of TypeScript Generics (`<T>`) allows the `fetchData` function to be agnostic about the data it retrieves, while the consumer of the function (`loadProduct`) gets full type support. This pattern is essential when migrating large JavaScript to TypeScript codebases where API calls are frequent.

Section 3: Advanced Techniques and DOM Manipulation

When working with the DOM, TypeScript forces you to acknowledge that elements might not exist. In JavaScript, `document.querySelector(‘.input’).value` might throw an error if the element isn’t found. TypeScript considers `document.querySelector` to return `Element | null`. This introduces us to TypeScript Union Types and TypeScript Type Guards.

DOM Interaction and Type Assertions

To interact with specific HTML elements (like inputs or canvases), you often need to tell TypeScript exactly what type of element you are selecting. This is done via TypeScript Type Assertions (casting).

// Selecting a DOM element

const inputElement = document.querySelector('#user-email');

// TypeScript Error: Object is possibly 'null'. Property 'value' does not exist on type 'Element'.

// console.log(inputElement.value);

// Correct approach using Type Guards and Assertions

if (inputElement) {

// We assert that this is specifically an Input Element to access '.value'

const emailInput = inputElement as HTMLInputElement;

emailInput.addEventListener('input', (event: Event) => {

const target = event.target as HTMLInputElement;

console.log("Current email:", target.value);

});

}

// Advanced: Creating a custom Type Guard

function isHTMLInputElement(element: Element | null): element is HTMLInputElement {

return element !== null && element.tagName === 'INPUT';

}

// Usage of the custom guard

if (isHTMLInputElement(inputElement)) {

// TypeScript now knows 'inputElement' is definitely HTMLInputElement inside this block

console.log(inputElement.value);

}Utility Types and Complex State

As your application grows, you might need variations of your base types. TypeScript Utility Types like `Partial`, `Pick`, and `Omit` are incredibly powerful for state management, such as in TypeScript Redux or Context API patterns.

For example, when updating a user profile, you might only send a subset of fields. Instead of creating a new interface, you can use `Partial`.

interface UserProfile {

id: string;

email: string;

displayName: string;

preferences: {

theme: 'light' | 'dark'; // TypeScript Union Types

notifications: boolean;

};

}

// We want a function that updates the user, but doesn't require all fields

function updateUser(id: string, changes: Partial<UserProfile>) {

console.log(`Updating user ${id} with`, changes);

// Logic to merge changes...

}

// Valid call - we only provide email and preferences

updateUser("u_999", {

email: "new@example.com",

preferences: {

theme: 'dark',

notifications: true

}

});This section highlights how TypeScript Union Types and Utility types reduce boilerplate code, a common complaint in TypeScript vs JavaScript debates.

TypeScript and Webpack logos – How to Setup a React App with TypeScript + Webpack from Scratch …

Section 4: Best Practices, Tooling, and Optimization

Adopting TypeScript is not just about changing file extensions from `.js` to `.ts`. It involves setting up a robust environment using TypeScript Configuration (`tsconfig.json`) and adhering to strict standards.

Strict Mode and Configuration

To get the most out of the language, you should enable TypeScript Strict Mode in your `tsconfig.json`. This turns on flags like `noImplicitAny` and `strictNullChecks`. While it makes the learning curve steeper, it prevents the “false sense of security” that comes from loose typing.

Common Pitfall: Avoid using the `any` type. Using `any` effectively disables the type checker for that variable, defeating the purpose of TypeScript. Instead, use `unknown` if the type is truly dynamic, as it forces you to perform type checking before using the data.

The Ecosystem: Linting and Testing

A modern stack usually includes TypeScript ESLint and TypeScript Prettier to enforce code style and catch potential bugs that the compiler might miss. For testing, Jest TypeScript (using `ts-jest`) is the standard for writing TypeScript Unit Tests.

Build Tools

TypeScript and Webpack logos – How to use p5.js with TypeScript and webpack – DEV Community

Modern build tools like TypeScript Vite and TypeScript Webpack handle the compilation process (transpiling TS to JS) incredibly fast. If you are building a library meant to be consumed by both TS and JS users (similar to the approach taken by modern package maintainers), you need to configure your `package.json` to export type definitions (`.d.ts` files). This ensures that consumers of your library get IntelliSense support even if they are using plain JavaScript.

Performance Considerations

TypeScript Performance is strictly a compile-time concern. TypeScript compiles down to JavaScript, so it does not add runtime overhead. However, the way you write code changes. By using static analysis, you can optimize algorithms and data structures (like using TypeScript Enums or const assertions) more confidently, knowing the compiler will catch regressions.

Conclusion

Migrating from JavaScript to TypeScript is a significant investment, but one that pays dividends in code quality, team scalability, and application stability. We have covered the essentials—from TypeScript Basics and TypeScript Classes to handling asynchronous API calls and DOM manipulation. We also touched upon the importance of the ecosystem, including TypeScript ESLint and modern build tools.

As the web ecosystem evolves, with tools handling increasingly complex tasks like compact data formatting and LLM integration, the precision of TypeScript becomes indispensable. It bridges the gap between the flexibility of JavaScript and the reliability required for enterprise-grade software. Whether you are looking to refactor a legacy project or start a new TypeScript Next.js application, the best time to start typing your code is now.

Start small: rename a file to `.ts`, fix the errors, and gradually enable stricter settings. Your future self (and your team) will thank you for the clarity and safety that TypeScript provides.