Well, I have to admit, I used to be a bit of a duplicator myself. You know, defining that TypeScript interface for the API response, and then writing a separate validator just to make sure everything was hunky-dory at runtime. It’s a tale as old as time, really. But you know what they say – the compiler should do the heavy lifting.

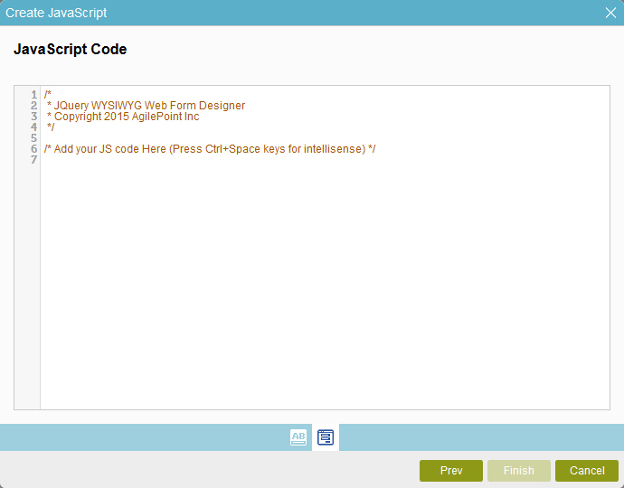

Two sources of truth, one inevitable drift. Yep, been there, done that. And let me tell you, that production incident you mentioned – running Node 23.2.0 on the backend and having a “guaranteed” string field come through as null? That’s the kind of thing that’ll make you reevaluate your whole approach.

The TypeScript compiler is a beast, no doubt about it. But it’s got a blindspot when it comes to IO. It just trusts you, you know? “Oh, you say this is a User? Alright, cool, I believe you.” Not the best approach, if you ask me.

Code Generation over Runtime Interpretation

Now, this build-time compilation for contracts – that’s the way to go, if you ask me. Take that JSON Schema, feed it into a compiler, and bam! You’ve got your TypeScript type and a super-optimized validator function, all in one neat little package. No libraries, no runtime overhead. Just good old-fashioned, lightning-fast boolean checks.

And the best part? When you generate the TypeScript type from the same source as the validator, they can’t diverge. You’re practically bulletproof against those pesky “string vs. null” bugs. If the schema changes, the build regenerates everything, and TypeScript will let you know if you didn’t handle that change properly.

Handling the Tricky Stuff: Discriminated Unions

Ah, yes, the bread and butter of modern TypeScript development – discriminated unions. That’s where this approach really shines. Instead of writing that switch statement manually (talk about tedious), the compiler can generate it for you, ensuring that your runtime logic matches your TypeScript narrowing blocks perfectly.

Branded Types and Coercion

And don’t even get me started on those “branded types” – using TypeScript to distinguish between two strings, like UserId and OrderId. Runtime validators usually just see “string,” but with this approach, you can generate those nominal types and keep the runtime check nice and simple.

Is It Worth the Setup?

I know, I know, another build step? Who wants that, right? But trust me, once you get this set up, the mental overhead is practically zero. Edit a schema file, hit save, and boom – your types are updated. No more writing validators, no more debugging “why did Zod say this was okay but TS is angry?” issues.

Sure, for a small side project, Zod is probably fine. But if you’re working on a system where performance matters, or where type safety across network boundaries is critical, this is the way to go. The TypeScript compiler is powerful, but it needs a little help crossing that bridge to runtime. Build that bridge yourself, my friend.