I looked at a Pull Request yesterday that made me want to close my laptop and walk into the ocean. It wasn’t the logic—the logic was fine. It was the types. Specifically, the sheer volume of redundant, copy-pasted interfaces cluttering up the types.ts file.

My coworker had defined a User interface. Then a UserForUpdate interface (same thing, but optional fields). Then a UserSummary (just name and ID). Then a UserResponse (user plus a status code). It was exhausting just scrolling through it.

I left a comment: “Just use utility types.”

The response? “I thought those were just for library authors.”

No. No, they are not. If you are writing standard application code in 2026 and you aren’t using TypeScript’s built-in utility types, you are wasting your time. I’m not saying that to be mean. I’m saying it because I wasted years doing exactly the same thing. I used to hand-roll mapped types for every slight variation of an object until I realized the language team already did the hard work for me.

The “Update Form” Nightmare

Let’s start with the most obvious one. You have a massive object. You need a function to update it. But you don’t want to force the user to pass in every single property just to change a display name.

I used to write a separate interface for this. It was dumb. Partial<T> takes an existing type and makes everything optional. It’s perfect for patch operations.

interface UserConfig {

id: string;

theme: 'dark' | 'light';

notifications: boolean;

retryAttempts: number;

apiKey: string;

}

// The old, painful way:

// interface UpdateConfigParams {

// theme?: 'dark' | 'light';

// notifications?: boolean;

// ... and so on

// }

// The way that keeps your sanity intact:

function updateUserConfig(current: UserConfig, changes: Partial<UserConfig>) {

// 'changes' can have 0, 1, or all properties of UserConfig

// but it CANNOT have random properties that don't exist.

return { ...current, ...changes };

}

// Usage

const myConfig: UserConfig = {

id: 'u_123',

theme: 'dark',

notifications: true,

retryAttempts: 3,

apiKey: 'xyz'

};

// Valid - I only want to change the theme

updateUserConfig(myConfig, { theme: 'light' });

// TypeScript screams at me here (as it should)

// updateUserConfig(myConfig, { themee: 'light' }); // Typo caughtThis seems basic, but I still see people manually defining “Optional” versions of their types. Stop it. The moment you change the original UserConfig, your manual update type is out of sync. Partial keeps them locked together.

Cleaning Up API Responses

Here’s a scenario I ran into last week. We have a backend entity that includes sensitive data—password hashes, internal flags, that sort of thing. When we pass this data to a frontend component, we need to make sure we aren’t accidentally leaking that stuff, or at least that the type definition doesn’t make it look like that data is available.

You’ve got two main options here: Pick and Omit. I have a love-hate relationship with Omit, but let’s look at Pick first because it’s safer.

interface DatabaseUser {

id: string;

email: string;

passwordHash: string; // dangerous

adminNotes: string; // private

avatarUrl: string;

lastLogin: Date;

}

// I want a type for the UserCard component

// It only needs the avatar and email.

type UserCardProps = Pick<DatabaseUser, 'email' | 'avatarUrl'>;

const renderUserCard = (user: UserCardProps) => {

// I can access user.email

// I CANNOT access user.passwordHash

console.log(Rendering ${user.email});

};I prefer Pick (allowlisting) over Omit (blocklisting) usually. Why? Because if I add a new sensitive field to DatabaseUser later, Pick won’t include it by default. Omit would include it until I manually exclude it. That said, sometimes you just want to drop one specific field from a massive object.

Just be careful. I once used Omit to remove an ID field, then refactored the ID field name, and the Omit silently stopped working because the key didn’t exist anymore (though modern TS is better at catching this).

The “I Don’t Control This Library” Problem

This is where things get interesting. You’re using a third-party library. It exports a function, say fetchComplexData(), but it doesn’t export the return type interface. It just returns Promise<SomeInternalType>.

I’ve seen developers copy-paste the type definition from the library’s source code into their own project. Please don’t do that. It’s brittle. If the library updates, your code breaks.

Instead, combine ReturnType and Awaited. This saved my bacon on a project where the documentation was… let’s call it “aspirational.”

// Imagine this is from 'some-crappy-lib'

async function getThirdPartyData(id: string) {

return {

data: {

items: [1, 2, 3],

meta: { page: 1, total: 100 }

},

status: 'ok'

};

}

// I need to write a function that processes just the 'data' part of this response.

// But I don't have a type for it!

// Step 1: Get the return type of the function (which is a Promise)

type FullResponsePromise = ReturnType<typeof getThirdPartyData>;

// Step 2: Unwrap the Promise to get the actual object

type FullResponse = Awaited<FullResponsePromise>;

// Step 3: Extract the specific part I need

type DataPart = FullResponse['data'];

// Now I can write my function safely

function processData(input: DataPart) {

input.items.forEach(i => console.log(i));

// TS knows 'input' has 'items' and 'meta'

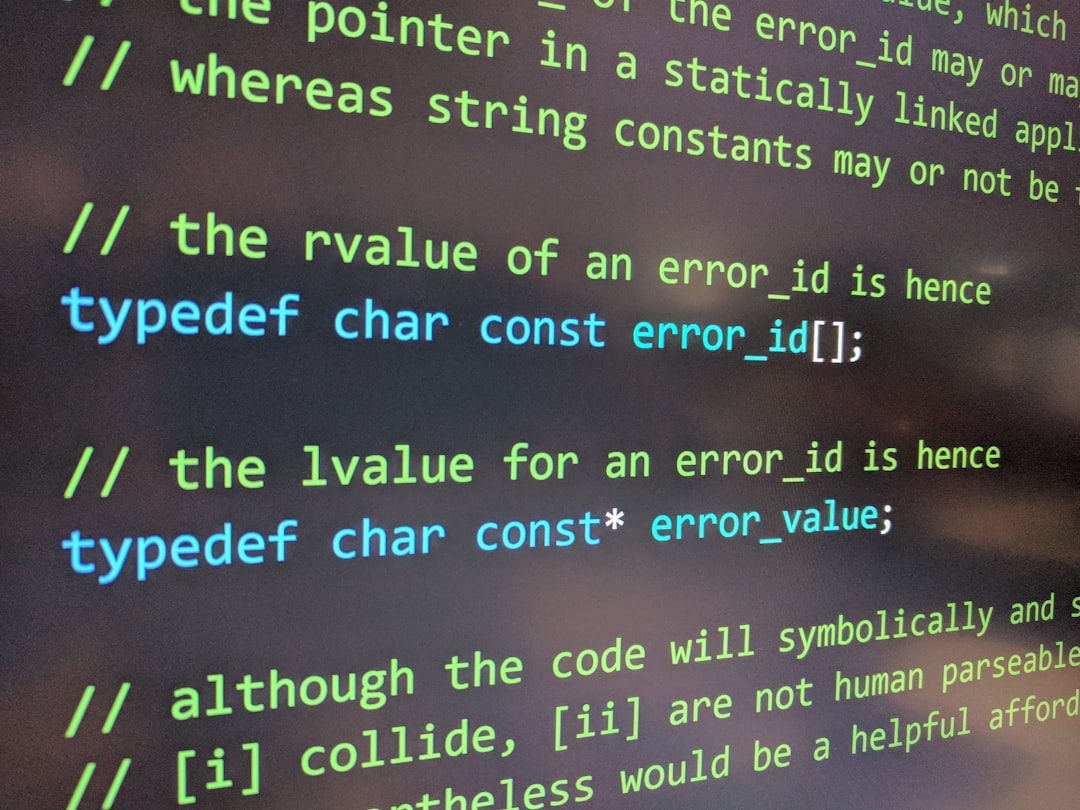

}Awaited is relatively new-ish (I think it landed in 4.5?), but it’s indispensable for async workflows. Before that, we had to write some horrific conditional types to unwrap promises. Now it just works.

Making DOM Events Less Painful

I hate writing DOM event handlers. You either type the event as any (lazy) or you spend ten minutes Googling “what is the type for a mouse click on a button vs a div”.

You can use Parameters to infer what a function expects. This is super useful when you’re wrapping native browser APIs or library functions and want to mirror their signatures exactly.

// Let's say I'm wrapping addEventListener to add some logging

function addTrackedListener<K extends keyof WindowEventMap>(

type: K,

listener: (this: Window, ev: WindowEventMap[K]) => any,

options?: boolean | AddEventListenerOptions

) {

console.log(Adding listener for: ${type});

const wrappedListener = (ev: WindowEventMap[K]) => {

console.log(Event triggered: ${type});

listener.call(window, ev);

};

window.addEventListener(type, wrappedListener as EventListener, options);

}

// Usage

addTrackedListener('resize', (e) => {

// TypeScript knows 'e' is a UIEvent, not just a generic Event

console.log(e.detail);

});

addTrackedListener('keydown', (e) => {

// TypeScript knows 'e' is a KeyboardEvent

if (e.key === 'Escape') {

// do something

}

});Okay, that example is a bit dense, but the point is: I didn’t have to manually look up KeyboardEvent or UIEvent. I let TypeScript’s existing definitions flow through my code using generics and indexed access types.

One Last Trick: Required<T>

I feel like Required is the ignored sibling of Partial. Everyone uses Partial to make things optional, but rarely the other way around. I use Required specifically for configuration objects where the user can provide a partial config, but my internal code needs a full config object to run.

It acts as a sanity check. If I miss a default value during the merge, TypeScript yells at me.

interface AnimationOptions {

duration?: number;

easing?: string;

delay?: number;

}

const defaults: Required<AnimationOptions> = {

duration: 300,

easing: 'ease-in-out',

delay: 0

};

function animate(element: HTMLElement, options: AnimationOptions = {}) {

// Merge defaults with user options

// The resulting type is fully populated

const config: Required<AnimationOptions> = { ...defaults, ...options };

// Now I can use config.duration without checking if it's undefined

console.log(config.duration.toFixed(2));

}Don’t Over-Engineer It

There is a trap here. You can get so addicted to “type gymnastics” that you start writing unreadable code. I’ve seen types that look like minified JavaScript—nested ternaries, infer keyword abuse, recursive generic constraints. Don’t be that person.

Utility types are supposed to make your life easier, not make your junior devs quit. If you find yourself nesting Pick<Partial<Omit<T, K>>>, maybe just define a new interface. Readability still counts.

But for the everyday stuff—updating state, handling API responses, wrapping async calls—these tools are sitting right there in the global namespace. Use them. Your types.ts file will shrink by half, and you might actually enjoy reading your own code again.