In the vast ecosystem of modern web development, TypeScript has established itself as the standard for building robust, scalable applications. Among its many features, TypeScript Enums stand out as a unique and often debated construct. While interfaces and type aliases disappear entirely during the compilation step, Enums are one of the few TypeScript features that emit actual JavaScript code at runtime. This dual nature—acting as both a type-level contract and a runtime value—makes them a powerful tool, but also a source of confusion and potential performance pitfalls.

Whether you are working on a TypeScript React frontend or a complex TypeScript Node.js backend, understanding how to effectively manage constants is crucial. This comprehensive TypeScript Tutorial will take you beyond the TypeScript Basics. We will explore the internal mechanics of Enums, the controversy surrounding their usage in modern TypeScript Projects, and the “Union Types vs. Enums” debate that dictates TypeScript Best Practices today.

Understanding the Core Concepts of TypeScript Enums

An Enum (short for Enumeration) allows a developer to define a set of named constants. Using enums can make it easier to document intent, or create a set of distinct cases. TypeScript provides both numeric and string-based enums.

Numeric Enums

By default, enums are numeric. If you do not initialize them, they auto-increment from zero. This behavior is familiar to developers coming from languages like C# or Java. However, you can also manually set the starting value or assign specific values to all members.

Here is a basic example representing the state of a task in a TypeScript Application:

enum TaskStatus {

Pending, // 0

InProgress, // 1

Completed, // 2

Archived = 10 // 10

}

function getTaskLabel(status: TaskStatus): string {

switch (status) {

case TaskStatus.Pending:

return "Waiting for action";

case TaskStatus.InProgress:

return "Currently working";

case TaskStatus.Completed:

return "Done";

case TaskStatus.Archived:

return "Archived";

default:

return "Unknown";

}

}

const currentStatus: TaskStatus = TaskStatus.InProgress;

console.log(currentStatus); // Output: 1

console.log(getTaskLabel(currentStatus)); // Output: "Currently working"String Enums

While numeric enums are efficient, they can be hard to debug because a runtime value of 1 or 2 doesn’t convey much meaning in a console log or a database. TypeScript String Enums solve this by allowing you to initialize each member with a string literal. This is particularly useful for serialization, such as when sending JSON payloads in TypeScript Express or TypeScript NestJS APIs.

enum HttpMethod {

GET = "GET",

POST = "POST",

PUT = "PUT",

DELETE = "DELETE"

}

// Usage in a Fetch request wrapper

async function apiRequest(url: string, method: HttpMethod, data?: any): Promise<any> {

const response = await fetch(url, {

method: method,

body: JSON.stringify(data),

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' }

});

return response.json();

}

// Calling the function

apiRequest('/api/users', HttpMethod.POST, { name: 'John Doe' });String enums provide better readability during TypeScript Debugging. If you log the variable, you see “POST” instead of an arbitrary number.

Implementation Details: Under the Hood

To truly master TypeScript Advanced concepts, one must understand what the TypeScript Compiler (TSC) generates. Unlike TypeScript Interfaces or TypeScript Generics, which are erased during the build process, Enums generate a JavaScript object.

The IIFE Generation and Bundle Size

When you define a standard enum, TypeScript transpiles it into an Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE). This pattern is used to attach properties to an object. While functional, this approach has historically caused issues with “tree-shaking” (dead code elimination) in bundlers like TypeScript Webpack or TypeScript Vite.

Let’s look at the compilation output. Consider this TypeScript code:

// TypeScript Input

enum LogLevel {

Error,

Warning,

Info

}The TypeScript JavaScript to TypeScript conversion logic outputs the following JavaScript:

// JavaScript Output

"use strict";

var LogLevel;

(function (LogLevel) {

LogLevel[LogLevel["Error"] = 0] = "Error";

LogLevel[LogLevel["Warning"] = 1] = "Warning";

LogLevel[LogLevel["Info"] = 2] = "Info";

})(LogLevel || (LogLevel = {}));Notice the assignment LogLevel["Error"] = 0 inside the square brackets? This creates a Reverse Mapping. It allows you to access the enum name via its value (e.g., LogLevel[0] returns "Error"). While this feature is clever, it results in code that bundlers sometimes struggle to remove if the enum is unused, potentially bloating your TypeScript Build.

Const Enums

To mitigate the runtime overhead, TypeScript offers const enum. These are completely removed during compilation, and their usage is replaced by the literal values inline. This is a significant TypeScript Performance optimization.

const enum Direction {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right

}

const move = Direction.Up;

// Compiled JavaScript Output:

// const move = 0; /* Up */However, const enum has limitations. You cannot look up the name of the enum value at runtime (no reverse mapping), and they can cause issues in certain build configurations like isolatedModules (often used in TypeScript Babel setups).

Advanced Techniques and Modern Alternatives

In recent years, a shift has occurred in the community regarding TypeScript Patterns. Many developers and teams prefer alternatives to standard Enums to ensure type safety without the runtime footprint. This is often discussed when migrating TypeScript vs JavaScript codebases.

The “Object as Const” Pattern

The most popular modern alternative is using a JavaScript object with a as const assertion combined with TypeScript Utility Types. This approach keeps your code idiomatic JavaScript while leveraging TypeScript Type Inference.

This pattern is highly recommended for TypeScript Libraries and TypeScript Frameworks development because it is fully tree-shakeable and predictable.

// 1. Define the object with 'as const'

const UserRole = {

ADMIN: 'admin',

EDITOR: 'editor',

GUEST: 'guest'

} as const;

// 2. Derive the Type from the object values

// equivalent to: type UserRoleType = "admin" | "editor" | "guest"

type UserRoleType = typeof UserRole[keyof typeof UserRole];

// 3. Usage in functions

function authorize(role: UserRoleType) {

if (role === UserRole.ADMIN) {

console.log("Access Granted: Admin Level");

} else {

console.log("Access Restricted");

}

}

// Valid

authorize('admin');

authorize(UserRole.EDITOR);

// Error: Argument of type '"superadmin"' is not assignable to parameter of type 'UserRoleType'.

// authorize('superadmin'); This technique leverages TypeScript Union Types and TypeScript Type Assertions (specifically as const) to create a robust system that feels like an Enum but behaves like a standard object.

Practical Async Example: API State Management

Let’s apply these concepts to a real-world scenario involving TypeScript Async operations and TypeScript Promises. Managing the state of an asynchronous request is a classic use case for discriminated unions, which often replace enums in modern TypeScript React or TypeScript Vue applications.

// Define states using a Union of String Literals (Simpler than Enums)

type RequestState = 'IDLE' | 'LOADING' | 'SUCCESS' | 'ERROR';

interface ApiResponse<T> {

data: T | null;

error: string | null;

status: RequestState;

}

// A generic async fetcher function

async function fetchData<T>(url: string): Promise<ApiResponse<T>> {

let result: ApiResponse<T> = {

data: null,

error: null,

status: 'LOADING'

};

try {

const response = await fetch(url);

if (!response.ok) throw new Error(`HTTP Error: ${response.status}`);

const jsonData = await response.json();

result = {

data: jsonData,

error: null,

status: 'SUCCESS'

};

} catch (err) {

result = {

data: null,

error: (err as Error).message,

status: 'ERROR'

};

}

return result;

}

// Usage

async function loadUserProfile() {

const profile = await fetchData<{ id: number, name: string }>('/api/me');

if (profile.status === 'SUCCESS' && profile.data) {

// TypeScript knows profile.data is present here

console.log(`User loaded: ${profile.data.name}`);

} else if (profile.status === 'ERROR') {

console.error(`Failed: ${profile.error}`);

}

}In the example above, using a union of string literals ('IDLE' | 'LOADING'...) is often preferred over a string enum because it simplifies the type definitions and requires no import of an Enum object to use the values.

Best Practices and Optimization

When deciding between Enums and their alternatives, consider the architecture of your project. Here are key guidelines for maintaining high-quality TypeScript Development standards.

1. Use String Enums for External Contracts

If you are sharing types between a backend (e.g., TypeScript NestJS) and a frontend (e.g., TypeScript Angular), String Enums act as a single source of truth. They ensure that if a status code changes from “ACTIVE” to “ENABLED”, you only update it in one place.

2. Prefer Union Types for Internal Logic

For internal component states or function parameters, TypeScript Union Types are lighter and more flexible. They work seamlessly with TypeScript Type Guards and control flow analysis.

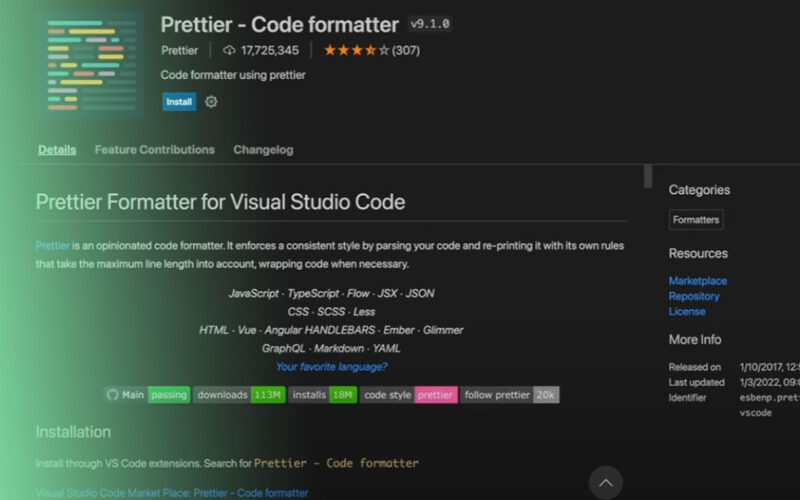

3. Configure ESLint and TSConfig

To enforce consistency, use TypeScript ESLint and TypeScript Prettier. You can configure rules to restrict certain types of enums. Furthermore, ensure your tsconfig.json is set to TypeScript Strict Mode. This forces you to handle all enum cases in switch statements, reducing runtime errors.

// .eslintrc.json example

{

"rules": {

// discourage numeric enums if you prefer string enums

"no-restricted-syntax": [

"error",

{

"selector": "TSEnumDeclaration:not([const=true])",

"message": "Don't use standard Enums, use 'const enum' or object 'as const'."

}

]

}

}4. Testing Enums

When writing TypeScript Unit Tests with TypeScript Jest, mocking Enums can be tricky because they are values, not just types. If you use the Object as const pattern, mocking becomes as simple as mocking a standard JavaScript object.

Conclusion

TypeScript Enums are a feature with a split personality. They offer a familiar syntax for developers coming from other strongly typed languages and provide a centralized way to manage constants. However, their runtime footprint and non-standard JavaScript behavior have led many in the community to adopt modern alternatives like Union Types and the as const object pattern.

Whether you choose to use standard Enums, const enums, or Union Types depends on your specific use case. For library authors and performance-critical applications, the as const pattern is generally superior due to better tree-shaking. For enterprise applications requiring shared contracts between services, String Enums remain a valid and powerful choice.

By understanding the compilation output, the performance implications, and the available alternatives, you can make informed decisions that elevate your TypeScript Projects. As you continue your journey from TypeScript Basics to mastery, remember that the best tool is the one that balances type safety, code readability, and runtime performance.